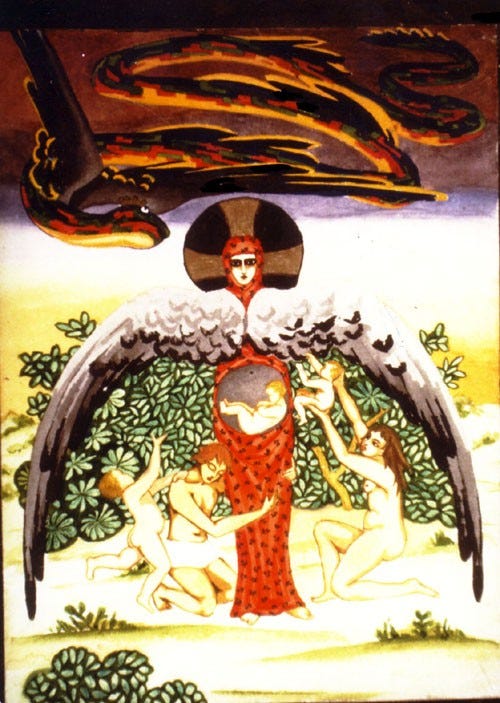

How Bulgakov’s Sophiology Pulls all of Creation Together Before the Foot of the Cross and into the Winds and the Fires of Pentecost

With a Brief Summary of Reading Section 1.3.e-f in The Bride of the Lamb

As far as I can tell, the most serious accusation among current theologians against Sergei Bulgakov’s sophiology is that it distracts us from the Son’s incarnation as the central point of contact between God and creation. This concern has been raised by some extraordinarily well informed readers of Bulgakov such as Protopresbyter Georges Florovsky and Fr. Marcus Plested. My own early experience in reading Bulgakov, however, has been with those who find that his sophiology leaves us all with nowhere to go other than the manger, the cross, and the tomb of Christ where God meets us within our experiences of death itself. I have found that my work of reading and understanding Bulgakov has only brought the incarnation, birth, life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus Christ into deeper contact with my efforts at prayer, worship, and faithful living. At first, this was simply because sophiology dragged all of creation—including every detail of my life—relentlessly into the life of God where there was no possible place to turn but the cross of Christ. This all should be no surprise as God’s own Trinitarian life is described by Bulgakov as eternally sustained through “love’s power of the cross” wherein “the mutual sacrificial self-renunciation” (kenotic love) of each person of the Trinity for the others is what both eternally constitutes and unites them all. My second experience as a reader, was that Bulgakov clarifies the incredible power of the incarnation by closely tying incarnation to pentecost and saying, even, that incarnation prepares the way for pentecost over the course of fallen history. Bulgakov repeatedly pairs Incarnation and Pentecost (both capitalized in my translation of The Bride of the Lamb) as he describes God’s achievement of salvation and creation by God the Father through the Son and the Spirit. Of course, Incarnation and Pentecost also provide the structure of Bulgakov’s last trilogy as two other books, The Lamb of God and The Comforter, lay the groundwork for The Bride of the Lamb.

In my response here to the most recent reading section in this year-long series of reflections on The Bride of the Lamb, I will be distracted for a second time in a row by the wonderful symposium essays that have just finished being posted here regarding Marcus Plested’s book Wisdom in Christian Tradition: The Patristic Roots of Modern Russian Sophiology. In particular, in reading this most recent section of Bulgakov again (1.3.e-f), I’ve been thinking about how Bulgakov might respond to a comment in the final essay by the Maximus scholar Paul Blowers about the relation of Sophia to the Son and the Spirit. By focusing on this question, I’ll have to skip a lot of material for now because this current reading section (1.3.e-f) in The Bride of the Lamb was lengthy as well as extraordinarily rich (covering many subjects in a dense and spiraling style). Here are some of the main topics (on which I do plan to circle back in some upcoming bonus reading notes):

A contrast of divine “causation” (critiqued as a false concept) versus divine “creation” (upheld as reality)

Two kinds of “nothing” within the doctrine of divine creation

God’s self-positing (Thathandlung in the terminology of Fichte) and God’s kenotic love as the grounds of God’s triune life as well as the ground of creation

An account of creation in terms of the Genesis story with references to the beginning and the earth (as without form and void or tohu vabohu) and the light and the six days and the creation of humanity

A philosophy of time (and space) as non-existent in the abstract but as, in the concrete, “real because it has eternity itself as its content”

Despite these many gems, for this entry, I will focus on the several instances of Incarnation and Pentecost that showed up throughout this section of The Bride of the Lamb and consider what these have to do with critiques of Bulgokov’s Sophia as they have showed up most recently in the work of Fr. Marcus Plested as summarized by Paul Blowers.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Copious Flowers to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.