Rowan Williams and Peter Bouteneff on Schmemann, Bulgakov and Much More

Migrated from a Post Elsewhere on June 4, 2022

[Note: this was migrated here from a post elsewhere on June 4, 2022.]

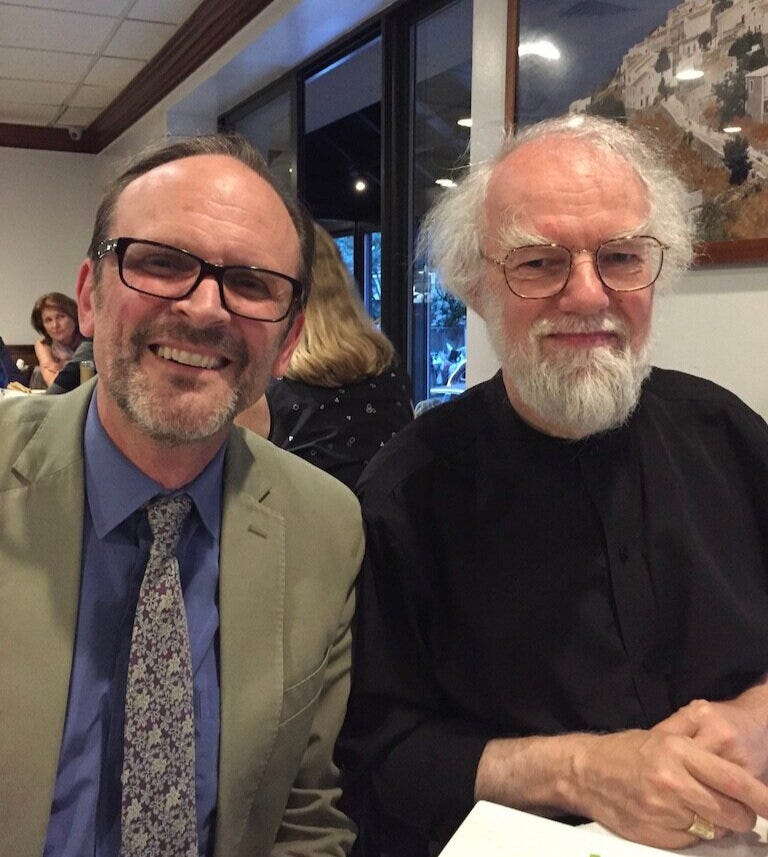

These two authors (one the student of the other) had a remarkable conversation on September 17, 2021 as part of the Luminous: Conversations On Sacred Arts podcast in an episode entitled "Rowan Williams: the Holy Arts and Holy Folly." I have recently posted reviews of books by each of them (How to Be a Sinner by Bouteneff and Looking East in Winter by Williams). Rowan Williams is the former Archbishop of Canterbury and among the most respected Christian thinkers alive today. Dr. Peter Bouteneff is the Director of The Institute of Sacred Arts at St. Vladimir’s Seminary (Yonkers, NY).

I make no commentary in this post but simply provide transcriptions of some highlights (with timestamps) from their conversation (which is well worth hearing in full, probably more than one). Both of them offer tremendous clarity and wisdom on a host of topics, including Vodolazkin’s novel Laurus, the Sophiology of Sergius Bulgakov and the significance of Alexander Schmemann's book For the Life of the World which Rowan Williams calls by its original title The World as Sacrament and says is “one of the most important theological texts I’ve read in my life.”

Here they are:

7:31

Bouteneff: “As you speak, I recall Christos Yannaras in his book The Freedom of Morality he has a chapter where he reflects on holy foolishness. And like you and like [Evgeny] Vodolazkin [author of Laurus], he ties it together with what you just now called ‘the fluidity of one’s identity.’ How we are never just ourselves. He links spiritual foolishness, in some way, with the spiritual fathers tradition where a spiritual counselor will take upon himself the sin of the confessor so that even sin is not one’s own as it were.”

Williams: “That’s a very important insight I think. I remember stories from the desert fathers which underline this. The idea that real spiritual fatherhood and motherhood is to be able to, well, to stand with and to stand for the people for whom you are responsible. That notion of being answerable for the people you love and the people you care for. I think that is at the heart of a great deal of what we say about holiness. I’m thinking of Mother Maria of Paris. Quite clearly, that is at the very center of her own witness, and of eventually her own martyrdom, the decision to be answerable, in her case, to be answerable for the stranger, for the Jewish refugee, and to stand in and to stand with at the most deep and costly level.”

9:21

Bouteneff: “I suppose one could say that a lot of hagiography partakes of the category of fiction—though one wouldn’t want to necessarily call it that—but there is a creative character to what one chooses to lift up and emphasize and perhaps even elaborate and even invent.”

Williams: “Yes, there has to be, I think. Just as the icon is not simply a portrait but reflects the particular ways in which a figure has not only been touched by the grace of God but has transmitted the grace of God to others. It’s as if looking at the saint and the icon, or the saint’s life, you’re not looking at arm’s length, you’re looking at what it is that they have made possible by the grace of God and at what it is, therefore, that opens the door for you as you confront them. So there is always going to be a bit of a tension between the close-focused historian, as you might say, and the hagiography. And there is a fictional element, not in the sense that you are just making stuff up, but of course the person writing the saint’s life is, as you say, selecting, adjusting, locating a figure both against the deep background of God’s grace and against the relationships that are triggered into life by the witness of the saint.”

14:15

Bouteneff: “It’s by way of [our sins] that the holiness is manifest or lived out?”

Williams: “Surely. I’ve heard people say that ‘the forgiven sins of the saints are our marks of glory in heaven.’ And I think that there is something very profound in that. You don’t look to a saint for, as I say, an unbroken success story. You look at them as examples of people who have really penitently received the grace God has to offer and allowed that grace to take them forward and transfigure.”

23:10

Williams: “Shakespeare ...writes plays that feel fresh every time you read them or see them because he is looking into a world that clearly exhilarates and bewilders him as it does us and opens the door but doesn’t presume to guide us or foreclose how we react but gives us endless opportunities to see. It’s that kind of opening onto an immense and bewildering and live-giving truth that, to my mind, gives all real arts its theological and spiritual importance.”

27:46

Williams: “The icon makes explicit, in some ways, what is going on in other kinds of art. Because the icon is where, as we are always told, is something that is not a self-contained work of art. It opens out. It invites you into an expanding perspective, a deep horizon. The figures in the icon come out of a depth that the four sides of the panel don’t contain. And that’s the important sense in which you can’t just walk around icons as you can walk around statues which is one of the things that I think makes them more intrinsically suitable, I think, for worship than statues.”

29:37

Bouteneff: “People want to kind of, maybe not inappropriately, keep icons in a separate sector of one’s engagement [with visual art].”

Williams: “I understand, and, to some extent, I endorse that. The icon is where this becomes explicit as part of the building up of the body of Christ in worship, and there is something quite distinctive about that. Just as there is something quite distinctive about the incarnate life of Christ and yet the incarnate life of Christ is what makes explicit the image of God that is spread abroad in the human creation at large. So there is something of that continuity that we need to affirm here.”

31:33

Williams: “I think [Fr. Alexander Schmemann’s] little book, The World as Sacrament, for all that it’s a very short book, it is to me one of the most important theological texts I’ve read in my life because it really does, with great economy and great perception, hold that vision together—without compromising the uniqueness of sacramental life—it does say there is a sacramentality flowing out from our focused sacramental action in the church to all our human engagement.”

32:58

Williams: “When the Holy Gifts are lifted up, it’s as if we are all able to say, ‘Ah, so that’s what it’s all about.’”

Bouteneff: “Indeed. Indeed.” [Apparently tearing up for just a moment.] I’m so glad you mentioned [Sergei] Bulgakov in this context because, although I haven’t penetrated him deeply enough, I’m aware of this very attractive line in his thinking that speaks of ...creaturely Sophianicity and our unique vocation to basically infuse the world with the divine. And that art ...and creatively is a major factor within that or instrument.”

Williams: “That is certainly what he believed. ...You have to cut through quite a lot of philosophical thickets to get to the essence of this. But as I’ve read him, he is saying there is something about our calling as creatures which is to belong in, to nurture, to affirm, to reinforce the connectedness, the interconnectedness, the harmony, the beauty of a creation which already, before we are on the scene, has begun to reflect its creator. And that seems to me a perfectly legitimate way of seeing how our discipleship, our Christian calling, is worked out. We are called—and I think Christos Yannaras and others would agree with this—we are called not just to be good, we are called to be in harmony. We are not called to score high marks in some ethics examinations. We are called to live in a way which is beautifully appropriate to the kind of creation we belong in.”

35:55

Williams: “Being a Christian ...means looking without any kind of protection or evasion into very, very hard places because only then do you really understand ...how deep the harmonies are to which you are called, deep and therefore often buried.”

Bouteneff: “[This helps us get to a place] where beauty can incorporate the disfigured and the troubling and the disruptive, because what is Christianity without the wound and the cross.”

Williams: “Without the wound, yes. And I suppose this takes us back to Vodolazkin’s novel again, Laurus, and many other fictions which invite us to see the beautiful in the broken.”

Loved that interview!