[Note: these reflections below rely on a much earlier reflection called “Undoing the Crucifixion of Jesus Christ” that I did not mention here but that would likely be helpful along side of these more recent thoughts in getting as sense for what I’m trying to share.]

A relatively new Christian named Miriam recently wrote to ask me if I believed what the young theologian Jordan Daniel Wood shared with me about God enabling us to change our pasts—that is if God can help us to make our broken and unfinished histories into complete and good enactments of God’s perfect will. Miriam noted that “something really traumatic happened to me years ago” and shared how she was “always fearful that even if I made it to heaven, that trauma would be a part of me that would always be a memory, something that could never be undone in me.” This made her “prefer non existence” to the thought of “having that [trauma] as a part of my identity forever.” However, she said that, even though the ideas shared by Jordan were “hard to believe,” they gave her “a completely new hope” that she had “never had before.” Miriam was responding to this summer 2022 interview that I did with Jordan where he shared things such as:

If becoming more like God means becoming less limited by time, then it’s as if the events which seem past to us are now opened to us like doors that we can walk through, which before we thought were impossible to walk through. Why does that matter? Because it opens up the potential or possibility of rectifying, of changing, of making right things which we in the past have made wrong.

It has been some time since I tried to pull together my thoughts on this topic, but this question from Miriam got me looking up some things again and talking with some friends. After our brief correspondence surrounding her questions, I asked Miriam if I could share our conversation, and she replied:

Of course, I would be so happy about that! I would be the first to want to read such future writings. You are more than welcome to use my story or experience in as much detail as you like—you absolutely have my permission. I’m even fine with you using my first name, Miriam and that I’m a young Christian who is inquiring into the Orthodox faith. If your writings in response to my situation can help others who have lived through similar traumas, that would be truly wonderful. God bless your work!

My first response to Miriam’s initial question, was that I did believe these things from Jordan and that I associated them with the calling by Christ for all of us to be perfect as God is perfect and to accomplish every good thing that we can possibly achieve—even up to the repayment of “the uttermost farthing” that Christ mentions in one of his many extreme warnings about what God expects from all of us. I also clarified that I have not had such trauma myself, so my ability to relate to her questions was based on much less significant sufferings of my own or of others who I have known. Finally, I shared a movie review called “Quentin Tarantino’s Cosmic Justice” by David Bentley Hart that felt relevant to her questions. Miriam found this essay about cosmic justice helpful and asked me next if she could “share a personal story of mine and why it causes me so much grief and makes me think that God can not ‘change the past’ in my traumatic situation.”

She hoped that I might be able to share my “perspective and thoughts” after hearing more of her experiences, and I replied:

As long as you are okay with me most likely having no answers or help to offer in any way. Serious trauma is a terrible burden to carry, and I’m not able to help much at all, sadly. But I will read when I can if you wish and try to share very basic thoughts if I have any.

Within another day or two, Miriam shared that, several years ago, she was sexually assaulted and told by a doctor afterward to take Plan B. In later years Miriam learned how this drug worked, and she came to worry that there might be a child awaiting her in heaven. This filled her with conflicted feelings:

While most Christians would say that is wonderful, the thought makes me feel even more trauma because I do not want a child that is the product of the rape that happened to me. I want nothing that is related to that evil man. ...Which takes me back to when Jordan Daniel Wood says that: “God will go back in the past and ...make it so that the terrible experience never happened and that what should have happened, will take its place.” But how can that be in the case of anyone who is raped and takes Plan B or has an abortion? If a child is brought into existence from it, then the rape can not be undone. God can not change the past in this case. Am I right? I’m so sorry if this was too personal. I just don't know anyone else who talks on these matters of God going back in the past. Either way, thank you for reading, and I’m grateful.”

I told Miriam that I would “reply briefly within a day or two” as well as saying how sorry I was to hear of such suffering:

There are no clear or easy answers at all with such brokenness and pain, but I will try to share what I understood Jordan to be saying and how it might apply in a case such as your own. I hope, separately, that you have some good Christian community and support in your life. In Orthodox Christianity, we would ask the new Saint Olga of Alaska to pray with us for such life burdens.

Miriam thanked me, and here is what I could think to share with her a few days later:

I do not think that it is appropriate or helpful to think about how history can be changed to completely make your suffering go away because you will have to learn in this life to carry the history of your terrible assault along with Christ who joined himself to our suffering to be there with us in everything that hurts us. Eventually, however, the monster who assaulted you will have been destroyed and you, for your part, will have learned to become as confident and strong as a perfect and pure daughter of God with no history of assault in your past because that monster has been destroyed. If there is a child from the sexual assault that you suffered in this fallen history, that child will also have a new history. It would be very foolish, I suspect, to talk or think about that new history. However, I will say that none of us are only the result of a sexual act with some kind of union of genetic material. We all need to be raised up and cared for and nurtured by whole communities of good and wise and loving people. We all have to have large families and villages of which we are the result. Ultimately, we all need the help of every other good creature that God has made in order to become who God has truly made us to be. This does not happen for any of us entirely within our fallen history. We only just barely get started on this work together here within our fallen and flattened and shattered time. In God’s good time, you and any child that you might have will find that many people are a help in seeing this child find their true history with you and, ultimately, not a history that includes any sexual assault.

She replied that these words brought some hope and comfort to her and asked God to bless me and my family. I also noted that, “if potentially helpful or of interest, here is contact info for an Orthodox Christian counselor who is trained in EMDR” and gave some contact information. Miriam was glad as she had been searching for an EMDR therapist for a while but had not yet found one who is an Orthodox Christian.

These interactions with Miriam brought the few things that I have found or heard about this topic vividly back into my mind. For example, since my brief correspondence with Miriam, I have talked a little myself with a trained EMDR therapist who is also an Orthodox Christian. EMDR stands for “eye movement desensitization and reprocessing” and is a technique that helps people to process traumatic memories. This therapist said that one of the aspects of a traumatic event is that it causes time to stop (or to become paralyzed and frozen) so that the trauma is no longer in relationship with the rest of the person’s ongoing life in any healthy or dynamic way that allows for change or maturation or healing. EMDR seeks to revisit the traumatic event (in very small increments of remembered time) and to bring any subsequent experiences of health, safety, and control back into contact with the traumatic event so that the damaged bit of memory gets reconnected or reintegrated with the rest of the person’s ongoing history—allowing any subsequent healthy experiences to start to heal the traumatic memory and to provide new understandings or perspectives on the event. This is, of course, not the same as changing our past, but it is another meaningful way of thinking about something similar. For my own part, I think it illustrates one of the ways in which such work on our past can begin in this lifetime with our work to heal and to repent.

This topic was brought up once, as well, within a recorded conversation between Salley Vickers and David Bentley Hart on November 7, 2022. It was Vickers who raised the topic:

I noticed in one of your recent substacks, you refer to a couple of books that are great favorites of mine, one of which is ...Tom’s Midnight Garden by Philippa Pearce which is a book that absolutely transformed my childhood because it explores, through the consciousness of a boy, the whole mystery of time: the way in which time isn’t linear, which is another thing which flows through my fiction and indeed your writing—the mystery of time. Though we live, apparently, in a linear way—our memories, our recollections—the way in which, when I worked as an analyst, I would watch a person’s whole past change as their attitude towards their past changed. So let nobody tell me that history is history. It isn't.

Hart replied emphatically:

Not only do I agree with this, I insist on it. This is a recurrent theme, it's true, in odd ways in my books—about the past being constituted in the future or in the present and being reconstituted and changed, really literally changed—even the book, recently, on Tradition and Apocalypse. ...Assuming that in quantum mechanics that the Everettian multiple universes are not real (or it doesn't matter how you see it), nonetheless, one of the interesting things about the double slit experiment that I always thought had implications far beyond the level of the quantum was that—at the moment of observation or of measurement, when either, really or apparently, the wave function collapses into the particle—the entire past history of that particle comes into being.

Vickers interjected “Exactly!” at this point, but Hart was just warming up:

Before observation, the particle or wave passes through both slits and neither and one and the other. All right, and if the observation occurs between the slits in, say, the photosensitive surface, not only do you no longer get the wave function from that point onward but now the particle has a history: it did pass through one slit or the other. It seems to me that, if that’s true at the level of the quantum realm, I see no reason to assume that consciousness is not always in the act of poetically reconstituting the past and that this is why we’re capable of spiritual healing and redemption and becoming other than just what we were and what we were determined to be by the past. Yes, I’m very much a believer that time is far more fluid and non-local than common sense would tell us it is, especially in the mechanized picture of reality.

After this, Vickers gave an example from her own past practice as a therapist in which the shared memory of a mother and daughter independently changed in the direction of a healed past experience together as the daughter was working to open her memories up to ongoing and continued goodness and love.

Before I close with a brief effort to relate and to synthesize some of these scattered ideas from various thinkers, I want to point out one more strand of thinking that I have associated closely with this concept of changing our past. This is George MacDonald’s “The Last Farthing” in his collection Unspoken Sermons. MacDonald says that Christ’s warning requires us to “arrange your matters with those who have anything against you, while you are yet together and things have not gone too far to be arranged” because “you will have to do it, and that under less easy circumstances than now.” Christ, as MacDonald lays it out, is warning us each that “there are means of compelling you” to make good on every little act of kindness and love that can possibly be imagined. As Dave Roney has astutely commented on this George MacDonald sermon: “What God is ever doing a man must learn to do.”

In the second half of his short sermon, MacDonald goes on to consider how a selfish soul who has no love for others can be destroyed and transformed from within as it is given over, in death, entirely to the utter loneliness of its own self-absorption. In death, MacDonald imagines a person with no world surrounding it with light or sound of any kind. Suspended in nothing but selfish desire, such a soul must eventually find within itself a desire for fellowship even if this is only with the most despised and hated neighbor from this hopeless soul’s memories. This eventual desire for any kind of companionship at all, however, will ultimately open up the closed-off heart to God’s presence and love again:

So might I imagine a thousand steps up from the darkness, each a little less dark, a little nearer the light—but, ah, the weary way! He cannot come out until he have paid the uttermost farthing! Repentance once begun, however, may grow more and more rapid! If God once get a willing hold, if with but one finger he touch the man’s self, swift as possibility will he draw him from the darkness into the light.

There is a contrast here between the long road back to God (in which we must completely accomplish every good thing that we have ever failed to do) and the powerful effectiveness of finally having opened ourselves up to being touched by God’s love. On the one hand, we must take “a thousand steps up from the darkness.” On the other hand, however, God draws us from the darkness into the light with a movement as “swift as possibility.” This is because, for most of us, “it takes long to think of God,” and we will search around in any other place for love before we consider letting God love us.

When each person, however, eventually recognizes all of the moments of their life as opportunities to receive the love of God and to respond to everyone around them with this same love, then we find that every monster who ever hurt us is being destroyed from inside out and is being transformed into someone who we never met within fallen time. Likewise, we are each transformed from monsters ourselves and can find all of the ways in which we have been inattentive to others or hurt and abused them so that we can will and do what God wills in every moment of our life.

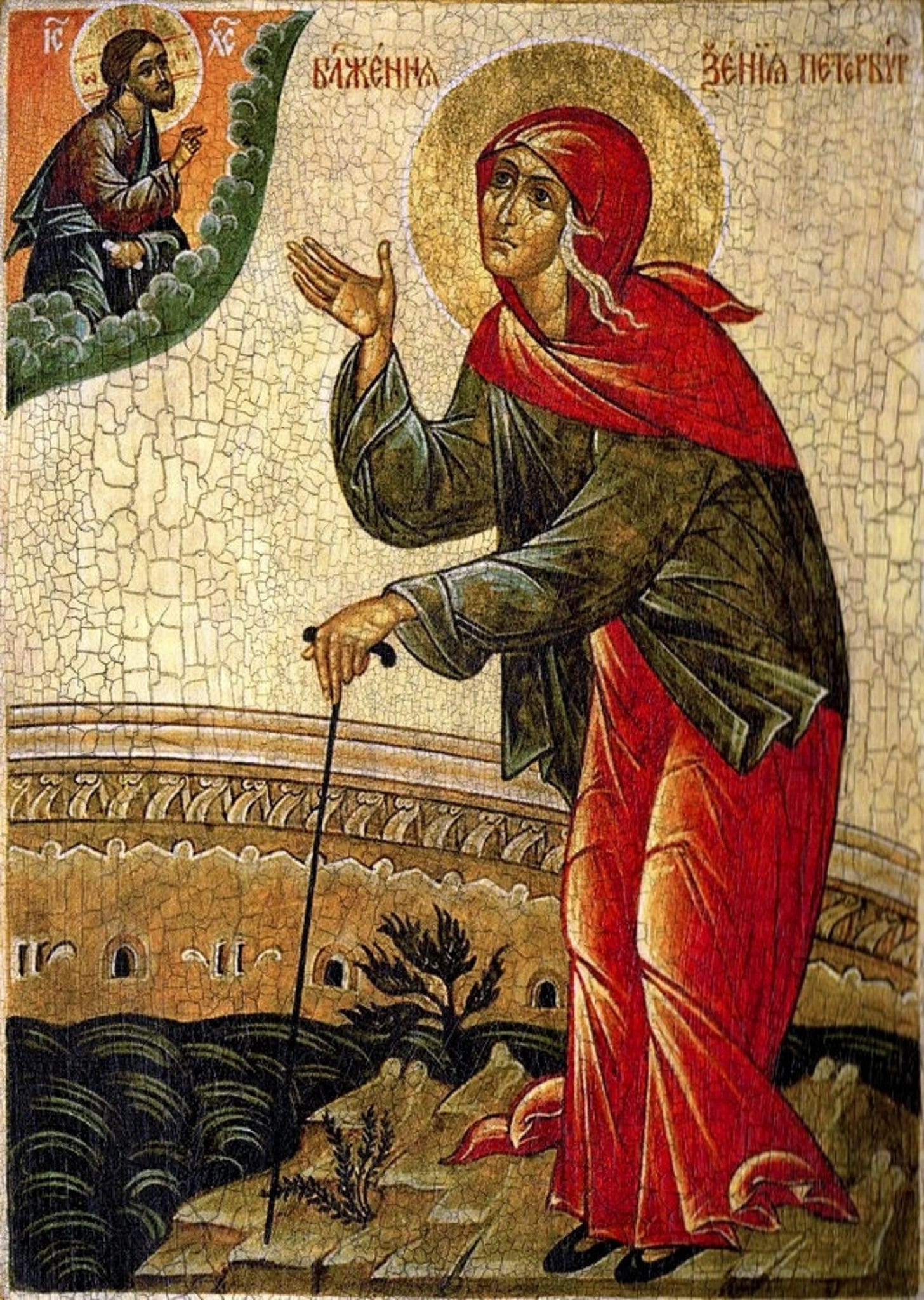

Every moment of this current fallen lifetime is a point of potential contact between God and multiple creatures of God. We so often fail to give and to receive. Instead of building a loving network of care and gratitude, we grasp and deceive and take and destroy. Instead of a past filled with life, we have a past filled with absence, death, and agony. However, as each of us heal in relation to Jesus Christ upon the cross with us, we begin to weave a new set of relationships that will relocate and rearrange past relationships and put lost people and lost times back into new and living relationships with all of God’s time. This remaking of our fallen past is not something that we can imagine or see from our current places within fallen time. However, this remaking of our broken past is something that we can start to do now and to receive from God in the presence of Jesus Christ. We can live in the light of God’s always-present presence and find a future step-by-step that begins to open the past up to us again. I think of saints such as Xenia of Saint Petersburg who dedicated their lives to a dead loved one and who tried to live on behalf of this lost person in some sense. After the foolish death of her husband Colonel Andrey Fyodorovich Petrov, Xenia wore his military cloak for the rest of her life and lived as a holy fool who did countless acts of goodness in secret on behalf of her lost husband. This is an extreme example of healing the past through a present life of loving and prayerful service that is literally reaching into the past and seeking to prayerfully and actively remake the life of someone who has already died. However, all of us—as we find opportunities to be present and faithful with those around us in our homes, neighborhoods, work places, and churches—will find that we are reaching into our own pasts and restoring opportunities for life that may have felt utterly shattered and lost to us. We can also, in small ways, reach into other’s pasts as well and help them find new ways of hoping for and perhaps even glimpsing something good where there has only been loss and devastation.

Fully realizing such a healing of our broken and often incomplete pasts rests ultimately with God and with all that can be revealed and offered to us only within a fully restored relationship with our loving Father. Through the love of Christ from the cross, God is destroying our enemies and oppressors and introducing each of us to all of our fellow creatures just as God made them to be.

Despite my best efforts, I cannot say it more boldly or clearly than Jordan Daniel Wood said it to me over two years ago:

We assume that because events have already happened in the past that they are done happening, but that’s a prejudice. That’s an assumption that, certainly in the light of some of the things we were just considering, maybe should be questioned.

...God doesn’t simply judge us just to judge or just to enforce a penalty, but his judgment is to bring about correction and truth and rectitude and reconciliation, as Paul says in Second Corinthians chapter five. As we all already kind of know in our own lives, reconciliation is a difficult and painful work. So you definitely still have the pain involved in judgment and punishment. It’s not fun. You don’t really wanna do it. But it also, then, would promise the perfection of things that we have made imperfect, even though they’ve happened in the past. And I don’t see why that’s an impossible prospect. St. Gregory, for example, he, at one point in one of his homilies says that, “in the end, everything that has come to pass will be as if it was not at all.” But he’s really specifically thinking about, I think, all of our regrets, all of our failures, all of our sin. And in other words of George McDonald, if I’m gonna borrow from him, “Salvation is good where evil was.” That includes when and where it was—not just “God can bring good out of evil” or “we can make the best of difficult things and regrettable things that have occurred” but that we can actually change what has occurred.

...And I would just throw out there as a potential, a point of reflection, you know, when we, even in this life, reconcile with someone we’ve hurt or try to repair damaged relationships, we already know how difficult it is just to even say things like, “I’m sorry” or “please forgive me for this” or “I did this.” And that is, in and of itself, perhaps, from my perspective, it’s just the prelude to the full restoration, which will be one in which you don’t just say, “I wish I had done this rather than that,” but you will actually go back and do that rather than what you did. And the only reason why that would be impossible is if the physical limits that we currently experience, if we take them for absolute limits of our experience. And for all of the reasons I’ve mentioned (and some others), I don’t think we have to assume that.

...One other way to put all this is that every moment is a work of God. ...Every act, every moment, every event, every word, every thought is also a work of God. And surely, if evil and sin and tragedies are not willed by God, then whatever God did will in its place has not yet occurred, even if it’s in the past from our perspective. And so what we get to do and what the work of judgment does, is finish the work of creation, even the creation of ourselves.

I’ve transcribed these words and read them over and over again in the months since I heard them. (I have even tried, foolishly once before, to write something with some relationship to them.) If you think that they are in line with what Jesus Christ reveals to us, which makes great sense to me, then the possibilities are astonishing. Without the loss of any good reality that we experience in this lifetime, we will eventually find that all kinds of things that we think are unalterable can be refashioned as the tiniest missed opportunities and connection points throughout the lifetimes of ourselves and all who we know are made complete and whole. We will have more people connected to making each of us who we truly are than we can currently imagine, and we will each have contributed more to the development and maturation of all those who we love than we could ever dream of in our current condition. In such an expanded web within God’s divine household, our sense of who our parents and our children truly were will likely be expanded in ways that would be foolish to try to imagine or describe right now. For now, we should simply pray for hearts that can receive God’s love for us. This is the way to repentance, thanksgiving, and new life in Christ. I’m grateful for the reminder recently from Miriam.

P.S. This passage from Wendell Berry came to mind for me today: “I imagine the dead waking, dazed, into a shadowless light in which they know themselves altogether for the first time. It is a light that is merciless until they can accept its mercy; by it they are at once condemned and redeemed. It is Hell until it is Heaven. Seeing themselves in that light, if they are willing, they see how far they have failed the only justice of loving one another; it punishes them by their own judgment. And yet, in suffering that light’s awful clarity, in seeing themselves in it, they see its forgiveness and its beauty, and are consoled. In it they are loved completely, even as they have been, and so are changed into what they could not have been but what, if they could have imagined it, they would have wished to be.” (A World Lost)

Man, this is the kind of concept that is so intrinsically significant for...everything...that it demands to be carefully considered. I remember reading or hearing Jordan on this topic somewhere at some time, but I clearly wasn't fully prepped to receive what he was saying at the time with the openness which it deserved. I think I ran aground on the obvious rocks of "changing the past feels cheap and like cheating." I completely get now that this is a much more nuanced supposal, not cheap at all, but thorough, and most of all, accomplishes what absolutely must be accomplished: the righting of every wrong, the making whole of every relationship, the abolition of evil, the theosis of every creature.

I wonder, though, if there are other ways to conceive of those things being accomplished without a remaking of the past, a re-writing of the story. Maybe, instead of the events of the past changing, their meaning and whole character changes. It may just be an aesthetic prejudice in me that still chafes at the thought of a re-writing of the story; like, why allow this version at all if learning things or growing in virtue and knowledge could (and may be in the age/ages to come) be accomplished differently? I'm really thankful for Benjamin in his comment bringing up Christ's wounds in the Resurrection, because I was going to as well. And I like Jordan's answer about this as a measure of the degree of humanity's total transformation such that when there are no longer any wounds in the whole of humanity, there will be no wounds on Christ. There's a poetry and a logic to that. But what if the wounds aren't *merely* that, a lingering sign of wounds still to be healed? What if they have another character to them, and are actually badges of love, their meaning having been elevated. What if, even after there is no guilt left, no shame, the wounds are retained as pure glories. I can't help thinking that there's a deeper principle signified by those wounds, a pattern of God's work, his "style" as C.S. Lewis was bold enough to call it in "Miracles": radical newness in Resurrection, yet with continuity to the old.

The same idea has been applied to the Saints, too, their special characters and charisms coming from their experiences, not least their sufferings. There are these great lines from an old Latin hymn (O qui tuo Dux martyrum) about my Patron, St. Stephen (whose name means crown):

The stones that smote thee, in thy blood

Made beauteous and divine,

All in a halo heavenly bright

About thy temples shine.

The scars upon thy sacred brow

Throw beams of glory round;

The splendours of thy bruised face

The very sun confound.

I think maybe there must be certain blessings and glories which could never arise or be brought about except through the *redeeming* and *transforming* of former pains. Isn't it conceivable that there are goods which could never have gotten their unique character without having been first transformed from evils? Something horrific at this stage and level which, as we grow in theosis, turns out to have been merely a tiny twist, a shape ("not worthy of comparison..."), that yields up a glorious pattern of growth that bears no resemblance to the twist but also could not have gotten its glorified shape without it? Instead of thinking of Creation as a static good that has been marred and must—as if in an afterthought—be rescued and reset and re-created, maybe Creation was always more like a story which was going to require its drama and plot twists in order to be brought to a glorious conclusion: the ultimate “happily ever after" that no creature could have guessed or imagined. Thinking of Creation as a story (a "narrative cosmology" we could call it?) doesn't chafe against my aesthetic sensibility as much, and still accomplishes those non-negotiables I mentioned above.

I don't want to be too confident in any of this, as you mentioned in your reply to Benjamin. They're just things I've been mulling over. Would love to hear your thoughts on them.

So encouraging, Jesse. And thanks from me to Miriam, and also to Benjamin who commented.

Dana