A Pharmacist who Has Joined his Patients for a Time (and Much More about all Manner of Peoples, Times and Places both Near and Far)

Pity as the Clarity of Vision in Tolkein's Moral Imagination and as the Gift of Peter's Tears

[Note: this was written with a high fever and is rather a serious disaster. However, there is some good material behind the subscription paywall, and I’m not going to clean it up much more.]

Today, I waited in urgent care for a little more than four hours with two visits for two children. My almost grown son was positive for the flu, and my seven year old daughter received antibiotics after a chest x-ray lead to suspicions of pneumonia. They filled the antibiotics at a place a little farther away than normal because it was the only one still open. However, on reaching the pharmacy, I found that only the storefront was open while the pharmacy was closed because of a pharmacist falling ill at the last minute. While walking our dog in between these trips, I found the landscape above where all of the trees have been cut down in the last couple of days starting where Scottsdale Tributary and Wyatt Tributary flow into Parkway Creek and running down the banks until a sandy little beach. It’s all for a necessary cause to update sewage lines and to protect the waterways. However, it is only a necessary cause and not a good cause (a distinction that I take seriously).

Early on Monday morning, I have been kindly asked to share a lecture with a gathering of Christian educators on the other side of the world that they entitled “Moral Imagination in Classic Literature: Pity’s Clarity and Tolkein’s Vision.” They most helpfully developed their topic request off of a short essay that I wrote called “Pity’s Clarity and Tolkien’s Vision for the Life of All” back in June of 2024. In this essay, I reflected on a remarkable comment by Gandalf that “I pity even Sauron’s slaves.” The good wizard clearly sees himself in both Saruman and Denethor who are reduced to Sauron’s slaves (or at least very nearly so in the case of Denethor) before each of their terrible deaths.

Reflecting as I have been a little today on Tolkien’s moral vision, therefore, the sudden sight of Parkway Creek’s familiar bank so deforested hit me even a bit closer to my heart. As you will know, Tolkien’s love of trees was profound:

In all my works I take the part of trees as against all their enemies. Lothlórien is beautiful because there the trees were loved; elsewhere forests are represented as awakening to consciousness of themselves.1

. . . The chapter called “Treebeard’” . . . was written off more or less as it stands, with an effect on my self (except for labour pains) almost like reading some one else’s work. And I like Ents now because they do not seem to have anything to do with me. I daresay something had been going on in the “unconscious” for some time, and that accounts for my feeling throughout, especially when stuck, that I was not inventing but reporting (imperfectly) and had at times to wait till “what really happened” came through. But looking back analytically I should say that Ents are composed of philology, literature, and life. They owe their name to the eald enta geweorc of Anglo-Saxon, and their connection with stone. Their part in the story is due, I think, to my bitter disappointment and disgust from schooldays with the shabby use made in Shakespeare of the coming of “Great Birnam wood to high Dunsinane hill”: I longed to devise a setting in which the trees might really march to war.2

Thankfully, I also finished reading, today, a book by Andrew Kern about education and how it should be modeled on the tabernacle of God. Briefly, reading this wise and gentle book today was a great relief and joy. (And I’ve been asked by The Russell Kirk Center to review it, so I’ll hopefully have a link to share one day.)

At the end of a full and somewhat more tumultus day than most, therefore, I sit to reflect on the moral imagination in classic literature, with a special eye toward Tolkien’s imagination.

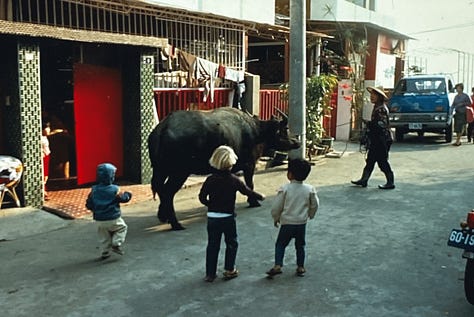

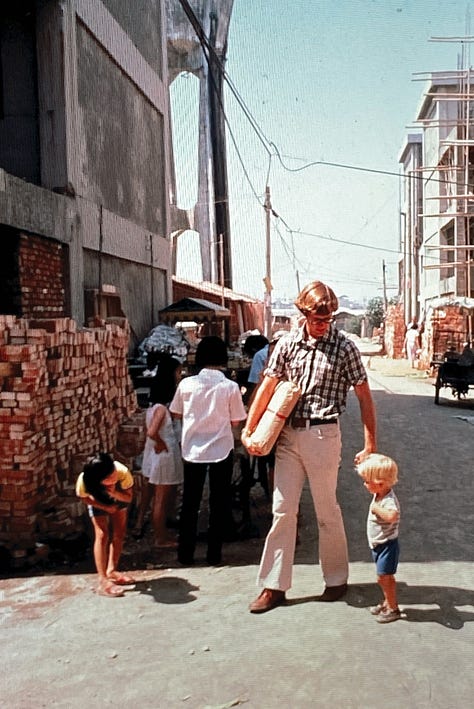

Yet, my mind wanders one moment more as consider the many other essays that I have started recently for this space including “Learning to Laugh with God” and one about my father’s recent return to Taiwan with my two youngest sisters—twins who are the same age as my oldest daughter. My father first lived in Taiwan during a semester abroad in college (1972, I think). He returned with my mother and I in 1977, the year of my birth and we lived there (with a steady arrival of eight more siblings for me) during the first eighteen years. A few mornings ago, I received a text message that simply read: “Hi Jesse, I was your neighbor 40 years ago.” As I texted with him, he was a boy who I spent endless hours with—ages three to ten—catching frogs, dragonflies, and snakes in the rice fields and banana groves. He had an extra thumb at that early age and could catch more frogs than any other kid. He was staying up late to share a Google photo folder with me containing beautiful pictures of my father and two sisters along with his mother and sister and nephew in some of the many places that they had taken my family members to visit in modernize Kaohsiung. The neighborhood in which my childhood friend and I had grown up side by side was a very different place:

However, as I said, all of these other musings are now laid aside, and my eyes are set on Tolkien and the moral imagination in classic literature. Dear readers, to hear more, you will either need to try out a subscription to this newsletter or find a top-secret gathering of educators from a land far away from Parkway Creek and the pharmacy that was closed this evening due to a pharmacists who has joined his patients for a time.

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Copious Flowers to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.