As the church seeks to continue teaching repentance and pursuing right theology, I strongly suspect that we will more and more fully repent of having declared Origen to be a heretic long after his own lifetime. With this uncanonical and unjust mistake—most likely foisted upon us with a bureaucratic sleight of hand by a few bickering scribes in Justinian’s court—we have cut ourselves off from one of the greatest teachers of our saints and a wellspring of sanctity and wisdom. To have condemned Origen as a heretic long after his death was a most unchristian act. However, I’m not here to wade in with the historical details regarding jealous slander in his own lifetime followed by centuries of both devoted readers among the church fathers and ongoing rivalry inside the imperial halls of power between several confused schools of discipleship (so called) on the one hand and several schools of bitter opposition on the other. Thankfully, there is more and more being written and talked about on these topics at both popular and scholarly levels.1

My goal in these reflections is to look at this error from the other direction, as something that the church can correct. What good might it do for the church to recognize and repent of this error? Of course, some readers will object that a layman such as myself should probably be focused on my own repentance (which is a rather vast need) and not fan my arrogance by calling upon my mother church to take up her vocation of repentance alongside me. As a very simple reply to an understandable question, I do not think it is possible to distinguish between these two things. What I fail to do, the church fails to do, and what the church fails to do is my own profound loss. One of the reasons why it feels strange, perhaps, for a layperson to write about how the church needs to repent is that we have most sadly misunderstood the nature of tradition. One of the most lively Christian voices in recent centuries, G. K. Chesterton, puts the key point here in vivid terms:

Christendom has had a series of revolutions and in each one of them Christianity has died. Christianity has died many times and risen again; for it had a god who knew the way out of the grave. ...The Faith is always converting the age, not as an old religion but as a new religion. This truth is hidden from many by a convention that is too little noticed. Curiously enough, it is a convention of the sort which those who ignore it claim especially to detect and denounce. They are always telling us that priests and ceremonies are not religion and that religious organization can be a hollow sham; but they hardly realize how true it is. It is so true that three or four times at least in the history of Christendom the whole soul seemed to have gone out of Christianity; and almost every man in his heart expected its end.2

No one doubts that Chesterton is defending tradition, but notice his point that, at the very heart of the Christian tradition, is a rejection of traditionalism and a recognition of continual death and rebirth. Incidentally, for a few other books unpacking all of this, consider Wilken’s The Myth of Christian Beginnings, Pelikan’s Jesus Through the Centuries: His Place in the History of Culture, and Hart’s The Christian Revolution and Its Fashionable Enemies (sadly mistitled Atheist Delusions) as well as his Tradition and Apocalypse. As Chesterton writes in a nearby passage, “a decidedly living tradition” is one that is defended by “the wonderful and almost wild vision of a Doctor of Divinity.” What does it mean to have a PhD in the subject of God? Chesterton is saying that anyone who claims to be devoted to the study of God must be among the most wild and wonderful of people. How many theologians like this have you read or heard? There are several today, but they tend to be shunned or disparaged by many.

We Christians want so badly to be brave and bold in the face of civilizational collapse, and we are ever ready to fight the culture wars yet again, but we would accomplish so much more by searching our hearts before God in prayer about what it would look like to consider church history and tradition as something dependent upon vigilant repentance and a commitment to an always wild and renewed life—animated by the Incarnation and Pentacost within our fallen world.

As is always the case in this broken and death-bound world, today is a wonderful time to be alive. A new study has just been released demonstrating how the dating of the Shroud of Turin is traceable by solid evidence to the time of Jesus Christ. C. S. Lewis—who had a small photograph of the shroud hanging on his bedroom wall close to where he said his prayers—would not have been surprised. A book releasing from the godless Yale University Press in a few days has four Greek gods and goddesses listening in on the debates among humans over the progress of modern science and the enduring mysteries of human consciousness and engaging among themselves in a divine argument (called by the author a “Platonic dialog”) about what is real and if we must acknowledge that Life and Mind point us toward a God whose imminence is bottomless and whose transcendence is limitless. If C. S. Lewis found the pagan goddess Psyche to be turning toward Christ in Till We Have Faces: A Myth Retold, I wonder if David Bentley Hart might find her ready to be an apologist for Christ in his forthcoming book All Things Are Full of Gods: The Mysteries of Mind and Life.

Certainly, there are also many reasons why this is a tragic time to be alive. It’s agonizing to read of the astonishing declines in flying insect populations across the entire globe. When I was a child, I spread white sheets out on the pavement under streetlights to watch the endless parade of insects that would land on the bright fabric and crawl across it. The variety of large moths were dizzyingly beautiful. I kept one giant water bug (Lethocerus americanus) for a few days, feeding her small frogs and naming her Cleopatra. Or consider the loss of wildflower names and craft guilds. We have no places left where the kind of human life together exists that would give local names to wildflowers such as those that used to arrive by the dozen for the most common of blossoms.

Or consider that every human civilization once boasted thousands of specialized guilds with silversmiths, cobblers, stonemasons, joiners, wheelwrights, potters, fresco painters, jewelers, tailors, pastry chefs, and such making a vast array of delicate and beautiful things out of the stuff gathered from their own valley and surrounding hillsides. Then, we rivaled the insects in our dignity and wealth, but now we make absolutely nothing. Instead, we all consume the same combination of hideous junk that is either mass-produced (sold to us from a few invisible warehouses that serve every town and city on the planet) or a gimmicky boutique product (exciting us to form another vapidly displaced but oh-so-hip niche market). When I talk to people about the loss of local culture, they inevitably start citing examples of niche markets as evidence that we’re doing fine.

In the face of all this devastation, our history on this planet has only one hope and that is that humans might once again learn to love their places together again. This is most likely to happen surrounding communities of worship with a willingness to take up our crosses of suffering together. In Psyche’s words (within Hart’s forthcoming book), we must learn again to “devote more time to the contemplation of living things and less to the fabrication of machines.” Christians have everything to offer in such matters if our communities would be willing to accept and to live within the reality, as Chesterton says, that “Christianity has died many times and risen again.”

I have no grand solutions amid the devastated lives that we share. I simply participate with my family and my parish and pray to find some modicum of gratitude despite being fairly sure that we are destroying our most gentle of planets and even that a terrible line of our world’s inevitable demise may have been crossed a long while back. However, when I do wonder what could possibly be done about it all, one very odd idea continues to return to my mind time and again. What if the church were to widely and formally repent for having mistakenly and grotesquely slandered Origen, the greatest teacher of our saints? What if we collectively took up and honored Origen’s own words regarding his commitment to the church?

I want to be a man of the church. I do not want to be called by the name of some founder of a heresy but by the name of Christ, and to bear that name which is blessed on the earth. It is my desire, in deed as in Spirit, both to be and to be called a Christian.3

What might be possible still in our future with such a turning back to one early point of failure so that we might take it up and recover from it to whatever extent that our lives together might yet allow? My own strong suspicion is that such an endeavor would slowly breathe an ancient and powerful life back into our church. Repentance in our personal lives can literally alter us and our loved ones, undoing past wrongs by the power of Christ and opening our eyes to deeper and deeper goods that we are missing and that we might pursue.

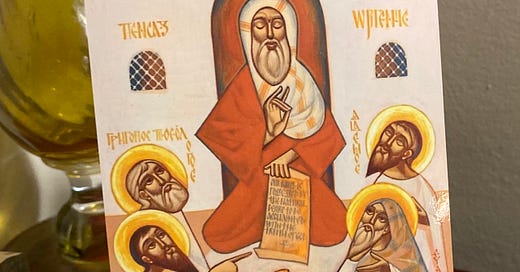

As should be obvious, I am not thinking that everything Origen taught was true. I’m not even imagining that we could possibly reconstruct what exactly Origen did teach from the battered and altered remains of his writings that have survived our tumultuous past. What I have in mind is simply the great deal of good that it would do for our own souls and for the ongoing life of our church should we undertake this repentance. And yes, Origen is an excellent example of many things. He was a model of learning from the most powerful pagan school of thought in his day, Platonism, while standing also as a clear alternative. His model was so effective, that Platonism exists in most of subsequent history simply as a rich strand within Christian theology. Christians today have much to learn from other ancient human faith traditions regarding how we can more and more fully articulate the truths of Nicea and Chalcedon for centuries to come, and we can benefit tremendously from Origen’s powerful example in these earliest years of our faith. Origen was also vigorous and balanced in his commitment to bold and creative thought as well as the need to keep in clear view the profound limitations that we face in regard to what we can know in our current condition. In all of this, we must of course honor his influence on great future leaders and teachers of the church, including many saints such as Athanasius of Alexandria and Gregory Thaumaturgus.

As we struggle together with our failures and needs in today’s world, the truth of Christ’s Incarnation and of the Spirit’s Pentecost have far more help to give, and we have a deeper and wiser inheritance upon which to draw as we consider what we have yet to learn and to articulate together in the light of God’s presence with us. One modest first step in receiving the fullness of our tradition would be to repent of our condemnation of Origen. So many other doors open up to us from our past more and more fully following this first step, and this opening up of the past is what it means to have a tradition. What traditionalists so sadly miss is that they are actually dead and closed off from tradition. Heretics are all traditionalists. They take one compelling strand of tradition and claim that it is the simple and logical answer. What Nicaea and Chalcedon did was to synthesize the fullness of multiple past traditions within definitions that could continue to unpack and uphold the profundity of the Incarnation and the Pentecost. May we throw off the heretical tendencies of traditionalism and open ourselves again to the fullness of our inheritance. This is my prayer in a nutshell. For others seeking this end, one simple place to start is to remember, on each 22nd of April, the feast day of Saint Leonides of Alexandria who is Origen’s martyred father. Leonides and Origen, pray for us.

Consider scholars like Mark Edwards, John Behr, Krastu Banev, and Ilaria L.E. Ramelli along with more popular essays such as “Saint Origen” by David Bentley Hart, “An Open Letter to Dr Cyril Jenkins: Was Origen Condemned for Teaching Universal Salvation?” by Fr. Aidan Kimel, “How Origen Exposes Our Ecclesiastical Delusions” or “Origen the ‘Eunuch’: A New Castration Theory” both by Ambrose Andreano (a friend and fellow parish member).

The Everlasting Man in part 2 chapter 6 “The Five Deaths of the Faith.”

Cited here with a footnote referencing Theophilus of Alexandria and the First Origenist Controversy by Krastu Banev (2015), page 2.

Touch base with me at some stage soon.

“Til We Have Faces” is my favorite book and I am quite excited to see dear Psyche’s imminent return to the literary stage. Loved this entire reflection, thank you for sharing it.

On a side note though, have you read the study in question regarding the Shroud of Turin? After a bit of digging my impression is the recent headlines have been vastly over-sensational. My understanding (and I’m more than happy to be corrected if I’m misstating the reality of things) is that the conclusion of the study is not a new definitive measurement placing the shroud to Christ’s day, but instead a proposed and entirely conditional hypothetical scenario, which if true, would allow for that dating (the shroud would need to have been kept in an 22C environment with a humanity level of 55% for 13 centuries or so, only under those precise conditions would the aging of the cellulose in the fibers place the shroud around 2,000 years ago). The headlines, from what I’ve seen, are largely leaving out the fact that the proposed dating is conditioned upon unverified historical scenarios as opposed to a more traditional scientific measurement such as say, carbon dating.